This article first appeared in the May/Jun 2015 issue of WGM.

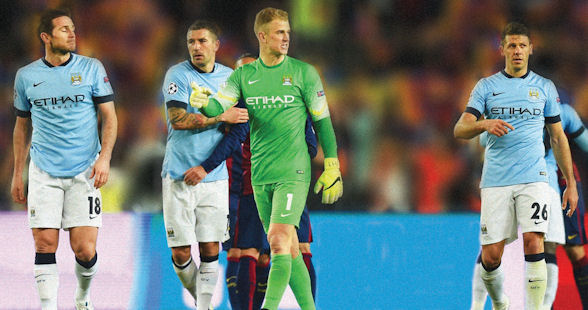

Twenty four hours after Arsenal fell agonizingly short of completing a miracle Champions League comeback against Monaco in the Round of 16, Manchester City’s slim chances of carrying English hopes further were emphatically destroyed by another master class from Barcelona’s Lionel Messi. Their departures, just a week after Paris St Germain stunned Chelsea, meant that twice in the last three years no English clubs have made it through to the final eight of Europe’s most prestigious club competition. The irony is that while the top Premier League clubs were struggling against the continental elites, Premier League bosses were congratulating themselves after completing a record new television deal worth £5.1 billion over three years. So is the EPL really the best league in the world as those astronomical figures lead us to believe or is it all a smokescreen?

There were four English representatives in the Champions League this season, with Liverpool the first to exit in the group stage. The other three – Chelsea, Arsenal and Manchester City – succumbed soon after in the first knock-out stage. The Gunners were perhaps the unluckiest of them all after producing a fine performance to beat Monaco 2-0 but paid the price for a sloppy 3-1 loss at home in the first leg. More importantly, that’s now five years in a row Arsenal has been eliminated at the exact same stage and 17 attempts at winning the Champions League without success for their veteran manager Arsène Wenger.

The all-English final featuring Chelsea and Manchester United in 2008 seems a distant memory now. What on earth happened to the Premier League of old which showed so much dominance in Europe during the first 10 years of the millennium?

Sir Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United were once a fearful force in Europe, particularly in 1999 when they won the treble by beating Bayern Munich at the Nou Camp. As foreign investments followed thick and fast into the Premier League, it very quickly established itself as the richest in the world in regards to purchasing power in the transfer market.

The Premier League reached its summit between 2007 and 2009. During this period nine of the 12 Champions League semi-finalists were English clubs. Liverpool and Manchester United finished runner-up in 2007 and 2009 respectively while United lifted the trophy after downing Chelsea in the all-English 2008 final.

However, the English dominance didn’t last long. Looking back, we can highlight one watershed moment as setting a new course – Cristiano Ronaldo’s £80 million move from Manchester United to Real Madrid. Ronaldo’s departure sparked a massive outflow of the best players from England to the European continent with more and more EPL players finding new homes in Spain and France. They have included the likes of Cesc Fàbregas, Gareth Bale, Xabi Alonso, Luka Modrić, David Luiz and most recently Luis Suárez. With rival European leagues becoming stronger, many of these players moved across to further their careers while others saw an opportunity to take advantage of the low tax rate Spain offers to foreign players.

The impact was quick to take hold. Having contributed 75 percent of Champions League semi-finalists the previous three years, not a single Premier League club reached the final four in 2009/10. And the past six seasons combined have seen England contribute just three of 24 semi-finalists! This season follows 2012/13 as two particularly forgettable years in which no English side even managed to reach the quarter-finals. Prior to 2013, British football had gone 17 straight years with at least one representative in the last eight – and let’s not forget that the previous occasion in which they had missed out in 1996 came at a time when the Premier League was only allocated one Champions League spot by UEFA. Since 2001/02 they’ve had four!

England’s woes in Europe bely its prosperity in terms of those soaring TV rights and the huge support it enjoys around the world. Asian audiences tune into the Premier League in droves each week but it makes you wonder whether we have picked the wrong league to watch. Should we be tuning into Spain’s La Liga or even Germany’s Bundesliga instead? Perhaps not. The Premier League remains the most watched league in the world and you only have to look at some of this season’s games – Leicester’s stunning 5-3 win over United, Tottenham downing Chelsea by the same scoreline or Liverpool’s dramatic 3-2 win against Spurs – to understand the attraction.

The recent auction of the EPL’s domestic TV rights saw Sky and BT Sports pay £5.1 billion to broadcast live matches from 2016 to 2019. Breaking that figure down, it will cost Sky Sports £11.07 million to show one live match and BT Sports £7.6 million. Many predicted this latest deal would actually be smaller than the previous one as a direct result of those poor Champions League results but in fact Sky will pay 83 percent more than they are under the current deal!

People love to watch the English Premier League. Sure, Barcelona, Real Madrid and Bayern Munich are much better technically and tactically but many football fans would prefer to watch a rigid Stoke City trying to suffocate Arsenal than Barca dazzling Valencia’s defense and scoring at will. And that’s the key to the EPL’s success among the public – they expect the unexpected.

Competition within the Premier League has never been so fierce. At the pointy end, at least six teams have spent the current season competing for a coveted top four finish, while so-called “minnows” have been waiting in anticipation to ambush the big guns. Southampton have defied all expectations by spending the entire season sitting high on the ladder among the likes of Arsenal, United and Liverpool. Burnley, who have looked doomed for much of the season while sitting last, managed a win and a draw in their two games against champions Manchester City. With just one slip-up potentially costing a side the title, as Steven Gerrard discovered last season, or an invaluable top four spot, it is now incredibly difficult to maintain a high level all year when playing in so many competitions. The schedule for those playing in Europe is stifling.

By contrast, Spain’s big guns regularly stroll past La Liga’s minnows without breaking a sweat. Already this season Real have put eight goals past an outclassed Deportivo la Coruna and scored five goals in a game on six separate occasions. Barcelona have scored six goals three times and five goals six times. Chelsea manager José Mourinho mockingly observed this very fact before the Champions League clash against Paris St Germain by claiming that his side’s training match at their Cobham facility the previous Saturday was tougher than Paris’ 4-1 demolition of Lens in Ligue 1. Sadly, there is actually some truth to that.

This doesn’t excuse the tactical naivety of some English clubs in Europe. Manchester City deployed two strikers against Barcelona at home, with some critics arguing Manuel Pellegrini would have been better served putting an extra man in midfield to wrestle some control away from the Spanish giants. Arsenal paid the price for their cavalier approach at home to Monaco with the French side tearing them apart on the counter attack.

And English clubs have also become inclined to favor attacking players over defensive ones, which becomes a problem when they suddenly have the likes of Messi, Ronaldo or Arjen Robben coming at them. A good example is the defensive midfielder role at Arsenal, which has looked sparse ever since Patrick Vieira left for Juventus in 2006. Adopting a policy based solely around attack provides great entertainment for the fans which is why the global audience continues to grow, but it remains a double-edged sword.

Meanwhile, the powers that be at Premier League headquarters aren’t taking much pity on their own despite pleas from the top managers to provide better protection through scheduling for their players. The Premier League has typically refused to adjust its schedule to aid rest and recovery as a result of European Cup games, the one exception being clubs playing in the Europa League on a Thursday being granted a Sunday rather than a Saturday league game the following weekend.

But the clubs can’t blame the governing body entirely. The high tax rate in England, emergence of continental football and increased internal competition have all contributed to the problem. And if it came down to a choice, would the big clubs really trade the riches the EPL’s global success has brought with a slightly better chance to go deep in Europe? As the saying goes, you can’t win them all.